An Invisible Government

An Invisible Government

by Natalia Ginzburg

I’ve always found it rather strange that after an election, nearly all the party newspapers proclaim victory even if they’ve been defeated. If I were a party leader, I would proclaim the truth in big red letters. If we had suffered a major defeat, the headline in my paper would read: “Major Defeat for Our Party.” I can’t see why every party newspaper instead finds it necessary to display exultant, triumphant headlines after each election. The few exceptions after the recent elections were remarkable indeed.

It will be pointed out that this is unimportant, since people read the voting returns and learn how things turned out in any case. It will also be pointed out that newspapers, whether partisan or non-partisan, carry far more murky and lethal lies. That is true. The triumphant headlines have become a convention, like the conventional hellos and goodbyes of a social call. People expect them and pay no attention. True enough. But if I were a party chief and my party had lost, I would go around shouting it from the rooftops. For in politics as elsewhere, the truth is salutary and invigorating.

It has been explained to me many times that the rules and procedures of politics are totally different from those of ordinary human life. It’s been explained that political power operates by delicate, subtle mechanisms that are highly sensitive and comprehensible maybe only to those who control them and can peer into their depths. The desire for truth, indeed any customary expectation of the human mind, has about as much weight on the machinery of political power as a swarm of gnats.

There are people who understand nothing of politics. I am one of them. There aren’t many such people, in fact there may be very few, since almost everyone manages to master a handful of essential notions that permit them to understand the terms and structures of politics. Certain people, however, not only understand nothing of politics but are incapable of thinking politically. They are even less able to express themselves in political terms. I am one of those. The people who do understand politics cannot begin to conceive of what we, the ones who understand nothing, are all about. So I want to explain, since after all, I know.

Thinking and expressing oneself politically means thinking and expressing oneself with a specific purpose in mind. Such a purpose might be aboveboard or corrupt; its ultimate goal might serve justice or oppression. Those who understand nothing of politics, on the other hand, think and express themselves without any goal whatsoever. It may be that their only goal is to explore and express their genuine thoughts. To the politically minded, such a goal seems pointless. And at times it seems utterly pointless to those who understand nothing of politics, too, which makes them despair. However, speaking their minds is the single thing in the world that they know how to do. At other times, they hope that what they say may strike a responsive chord in others. This is nothing like a specific goal, merely a stray hope.

When those who understand nothing about politics venture to speak of it, they either lapse into confusion and abstraction or talk nonsense. So it is more than likely that what I’m writing here is a string of nonsense. Still, I must confess that despite understanding nothing of politics, I nonetheless often feel an overpowering temptation to speak of it.

Beyond politics, there are countless other things about which I know and understand nothing, such as economics, or chemistry, or the natural sciences, or the exact sciences. But my lack of understanding of those subjects doesn’t disturb me. I get along fine without them. They proceed far from my life and almost never cross my mind. Understanding nothing of politics, on the contrary, feels like a serious disability. It pains and embarrasses me. People I’ve confided in tell me it’s simply laziness and resistance on my part. I am aware of being very lazy, and yet I have the sense that my utter failure to understand politics is not a question of laziness so much as a real disability.

When I was young, I thought that some time or other I would read books in order to gain some understanding and background in politics. After a while I noted that whenever I opened those books, my mind would dart away like a hare. And so I have never read a single line of them. I also noted, after a while, that all the novels and other books I had ever read were read without any fixed purpose.Even though I understand nothing of politics, political events do occasionally arouse my hatred and indignation or approval and passion. But these events don’t strike me as part of any coherent, lucid, and harmonious pattern; they always seem like fragments or splinters or bits of driftwood I’m clinging to like someone left floundering in a river at flood tide.

One of the very few political ideas within my grasp, perhaps the only one, I acquired when I was seven years old. It was explained to me what socialism was; that is, I was told it meant equal distribution of goods and equal rights for all. It struck me as something that had to be achieved right away. I found it strange that it hadn’t already been achieved. I remember the exact time and place where I heard these words, which were self-evident and crucial. To this day they still have the power to kindle a kind of flame in me. To this day I marvel that that state of affairs, namely, equal distribution of goods and equal rights, has not been achieved, and is apparently so complex and difficult to achieve.

When I have to vote, I follow emotional impulses; my inclinations are entirely of an emotional nature, as if I had to shake hands with a political party or kiss it on both cheeks. This is definitely not the proper way to vote. I know that. Each time, I’m given instructions, and each time, I cast them to the winds and instinctively follow only irrational affections and affinities. I find myself unable to vote for any party with resignation; I have to love the party I’m voting for. When I go to vote, that single rudimentary political idea that I possess, equal distribution of goods and equal rights for all people, flares up. I want to find out with absolute certainty who supports that, but since the explanations I get are conflicting and garbled, I end up voting blindly and emotionally.

People I know and trust have often told me that if equal rights and equal distribution of goods were attained, I would lose a part of my freedom, I wouldn’t write any more, and I would be terribly unhappy. This is because equal rights and equal distribution of goods don’t fall like manna from heaven but require a number of strategic and terrifying protections. In fact I, too, think that if I couldn’t write any more I would be very unhappy and might throw myself under a train. But I also think that our personal happiness or unhappiness should not determine our political choices. What works quite well for us personally may not work at all well for others. We want a better world, but it could be that this better world has no place for us. And yet, it is conceivable to regard our own personal destiny with some detachment. I don’t know if this kind of reasoning is political, that is, the kind of reasoning political people would accept. It is the reasoning of those who are desperate. I don’t know if there is a place in politics for the desperate. I imagine not.

Then again, maybe governments never run smoothly. Some, at any rate, are overthrown. The government I myself would want would be totally bland, insubstantial, invisible, a government so airy and invisible that we could forget all about it, not even notice that it exists. Under such a government, everyone would live well, everyone would have his rightful place and role and his rightful share of benefits and freedom. Granted, a government of this kind doesn’t exist in nature; nowhere are there any visible traces of it. In every existing government we find clamour, abuses of power, newspapers with triumphant, lying headlines, lies of every kind in public life. This being the case, someone like me, who understands nothing of politics, is compelled to think about politics and despair of ever understanding it, is compelled to envision something entirely different.

In truth, the airy, light, insubstantial and invisible government I envision might be a weak government, and in politics, weakness apparently has no chance at all of survival. It would be a weak government because in politics strength is noisy, intrusive, huge, and bloodthirsty. It would be a government without money or weapons, founded solely on a few values that are precious to the spirit, such as justice, truth, and liberty. But the word “truth” is seldom used in politics, and the justification offered for its absence is the nature of those very delicate, fragile, and sensitive mechanisms at the core of political life, which demand the most specialized and highly refined precautions. As for liberty and justice, we are told that for the time being they must be protected by weapons, police, and prisons; we are told it is essential to protect them by force, and meanwhile we have this irrepressible craving for weakness.

We are told that in the distant future, maybe after centuries of weapons and prisons, all will be well at last; there will be enough space and liberty for everyone. At last, we’ll no longer need to think in terms of nation-states, of masses of people and of governments, but only of our distinctive and solitary condition as human beings. But no one believes in the future any more. Years ago, we could believe in it; the music of tomorrow, authentic and intoxicating, rang in our ears. Then all at once the future collapsed before our very eyes. So while we long for a better world, we can’t project our longings to centuries from now. We don’t have centuries to wait any more, and even if we did, we have lost the will and the imagination to grasp what shape they might take. Right now we stubbornly love the present; we find ourselves bound by hoops of love to a time that gives no sign of loving us in return.

June, 1972

—Translated from the Italian by Lynne Sharon Schwartz

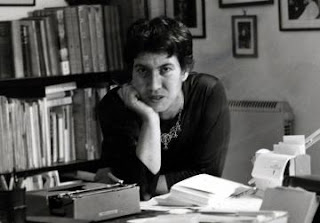

Natalia Ginzburg (1916-1990), one of the most renowned and distinctive voices in postwar Italian literature, was revered for her inimitable style and her unforgettable depiction of private lives in a disrupted social landscape. A prolific novelist, dramatist, and essayist, she is best known in this country for her novels

All Our Yesterdays,

The City and the House, and

Voices in the Evening, and her autobiographical work

The Things We Used to Say. The essays here are taken from

A Place to Live: Selected Essays of Natalia Ginzburg, published by Seven Stories Press and translated by Lynne Sharon Schwartz

“When I write stories I am like someone who is in her own country, walking along streets that she has known since she was a child, between walls and trees that are hers.”

“When I write stories I am like someone who is in her own country, walking along streets that she has known since she was a child, between walls and trees that are hers.”